The Lost City of Caversham

It’s long past time for the government to acknowledge both wrongs done and the good given back by the Slaters. A formal recognition (and even compensation) would not erase the past but it would at least make amends for the failures, pressures and neglect that cost this family so much, while honouring the lasting contribution they have made to the community.

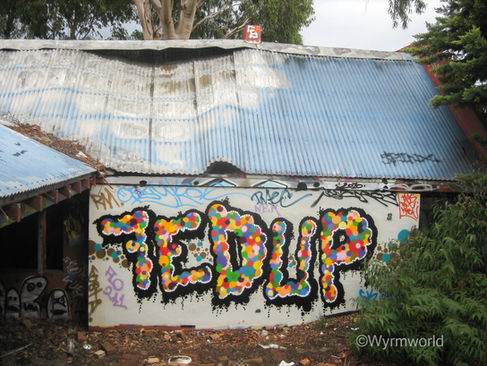

The Slater family’s former home, in what is now Henley Brook, became known as The Lost City after Flickr blogger Wyrmworld first adopted the nickname in May 2011. The name has since stuck and whilst its often described online as being located in Caversham, that description isn’t entirely wrong. Before suburb boundaries were redrawn in the 1990s and 2000s, the area was generally regarded as part of Caversham.

As with many abandoned places, rumours quickly circulated. One story stated by Wyrmworld, claimed the owner had been caught up in tax evasion, though I’ve never found any evidence to back that up. In my experience, Wyrmworld has generally been a reliable source, as evidenced in our earlier communications, so it’s possible he was simply repeating something that he’d heard at the time.

In reality, the property sat derelict for years before being purchased by Stockland in 2014 and absorbed into the Whiteman Edge housing estate, which now covers the land once home to the Slater family’s house and stables.

The Slater Estate

In the 1990s, William “Bill” Slater, a lifelong horseman, found himself fighting not only for his land but also for what he saw as the integrity of Perth’s planning system. His story, backed by environmental reports of the time, shows how the Ellenbrook development was pushed through against community wishes, environmental warnings and the long-standing vision that the Swan Valley and Whiteman Park would become the heart of Western Australia’s horse industry.

What began as a family dream for an equestrian estate in Henley Brook, became a battle against government deception, powerful developers and planning schemes that, in his eyes, sacrificed both community rights and the environment for short-term gain.

Slater’s equestrian roots stretched back to Belmont, where his family ran a riding school on Zante Road and held a lease on neighbouring Commonwealth land, which provided bridle paths and open country. Their riding school was taken away when the Commonwealth resumed the property for the proposed parallel runway at Perth Airport. The family fought the resumption for 13 years. Perth Airport’s planning history confirms that a second runway had been on the books since 1973, appearing in master plans throughout the 1980s and is still active today under the Commonwealth Airports Act 1996. After the loss of Belmont, the Slaters relocated to Henley Brook to keep their horse business alive.

Bill purchased 100 acres alongside Whiteman Park, zoned “special rural” for horse activities. He believed this would be the nucleus of the State’s equestrian industry. In 1984 he registered Bill Slater Bloodstock, which operated until 1996. His wife Christina Slater was a celebrated show horse and show jumping rider, representing Western Australia nationally and producing horses that set new records. Her champion, Countryman, cleared 6ft 3.75in to set a state record and went on to win at the Sydney Royal, Brisbane and Melbourne shows. She also produced other champions such as Beckdale and South Pacific. Christina was selected by the Equestrian Federation of Australia to train under Olympic coach Franz Mairinger, showing the Slater family’s deep contribution to the sport.

Planning Behind Closed Doors

Planning studies supported their choice of Henley Brook. The Stephenson Plan (1955) and the Semeniuk Report (1985) both earmarked the district for equestrian use. In 1978, the Shire of Swan amended its scheme to recognise this and the State even reserved land in Whiteman Park for a national equestrian centre (p.859) with the promise of federal funding (p.7985). Slater imagined Henley Brook as Western Australia’s version of Newmarket in England or the Curragh in Ireland, global centres where horses and viticulture thrived together.

But by the early 1990s, priorities had shifted. Developers, backed by government agencies, were pushing suburban expansion. At the centre was Ellenbrook, a dormitory suburb designed to house tens of thousands of people. To make it viable, highways had to be realigned, roads extended and rezonings pushed through. The key instrument was Metropolitan Region Scheme Amendment 950/33, which reserved land for the Perth–Darwin Highway and a transit corridor, while excising parts of Whiteman Park and State Forest No. 65 for urban and “special rural” development.

A parliamentary petition tabled on 6 April 1995, opposed urbanisation of the Swan Valley and Whiteman Park and called for boundaries to be redrawn to protect these areas. The committee heard from residents including Bill Slater, as well as from developers, planning officials and government agencies.

Slater called the amendment a betrayal. He argued it had been pushed through before essential environmental studies were complete, despite government promises to wait. Land that had been rural was suddenly reclassified as “urban deferred,” a planning term not recognised in local schemes but used to create the expectation of suburbanisation. This misled communities, raised land prices, encouraged speculation and pushed banks to treat equestrian holdings as doomed. Slater himself lost half his property as a result, when the bank foreclosed on it.

Water, Wetlands and What Was Lost

Slater’s biggest concern was water. Henley Brook sits above the Gnangara Mound, Perth’s largest groundwater source. Slater’s own bores showed the water to be pristine, yet he watched as Water Authority boundaries were shifted to suit development. His horse business had been rejected for supposed risks of manure leaching, while entire suburbs and a six-lane highway were approved despite greater risks from stormwater, fertilisers and road pollution. He said it was hypocrisy of the highest order. Once groundwater was compromised, it could never be restored.

Environmental authorities backed his concerns. The Environmental Protection Authority’s (EPA) Bulletin 753 (1994) warned that the highway alignment through Whiteman Park threatened wetlands, rivers and conservation reserves. It could also cause irreversible damage to drinking water supplies. Contamination, it said, would be almost impossible to clean once it reached the aquifer. Yet despite acknowledging the risks, the EPA conceded the road might still proceed for “social and economic reasons.” Public submissions mirrored Slater’s warnings: residents were not consulted, lifestyles would be destroyed and trust in government had collapsed.

The Ellenbrook Public Environmental Review (PER) of 1992 revealed more. The site contained 410 hectares of wetlands, yet only 90 would be preserved. The rest would be drained or converted into artificial basins. Wildlife relocation and token habitat protections were promised but the development would erase much of the area’s ecology.

Residents in Henley Brook, Belhus and nearby areas feared for their lifestyle. West Swan Road was already dangerous and Ellenbrook would make it worse unless new roads cut through their land. Some feared compulsory resumptions. Others worried that Homeswest’s involvement meant poor-quality housing. Fire services and local infrastructure were already stretched and the PER admitted the bushfire brigade lacked resources. Aboriginal communities also raised concerns about heritage.

Meanwhile, State Forest No. 65 was reduced by about 200 hectares for development and 28 hectares of Whiteman Park itself were rezoned from Parks and Recreation to Rural. Whiteman Park, originally acquired in 1978 to protect bushland and groundwater, was meant to remain untouched. For Slater, this proved the government was bending the rules for developers, whilst ordinary landowners were told no.

At the heart of it all was Ellenbrook Management Pty Ltd, a joint venture between Sanwa Vines Pty Ltd, a Japanese developer and Homeswest. Sanwa Vines had already created The Vines Resort and held most of northern Ellenbrook. In the joint venture, Sanwa Vines held 53% and Homeswest 47%, making Ellenbrook one of WA’s largest public–private projects. Slater believed the government bent over backwards to keep Ellenbrook afloat, even considering highway routes through Whiteman Park, while leaving existing residents like him powerless.

A Stolen Future

Slater's vision for the Swan Valley was very different. He saw a world-class equestrian and viticultural hub, a place of international standing like Newmarket or the Curragh, sustaining tourism, heritage and Perth’s water security. Instead, he watched that dream vanish under the weight of rezoning, broken promises and political expediency.

By the end of his evidence, he was clear: the process had been deceptive, residents misled and the environment sacrificed. He argued that five-acre equestrian estates would have been more sustainable and more profitable in the long run, while keeping the Swan Valley’s character intact. Instead, the land was consumed by a dormitory suburb.

The Slater property itself was eventually abandoned. In 2014, Stockland purchased it after nearly a decade of neglect, when squatters and vandals had left the buildings in ruins.

A Legacy Forged in Pain

The family tragedy was compounded years earlier by the loss of Bill and Christina’s only son, D’Arcy Slater. In June 1991, at just 13 years old, he drowned in the flooded Helena River while returning from football training at Guildford Grammar. Remembered as a lively student and talented athlete, his death inspired the creation of the D’Arcy Slater Foundation. The foundation and the D’Arcy Slater Scholarships support young people across Western Australia in sport, education and the arts, from WAAPA and WAIS to Tennis West and Riding for the Disabled. Guildford Grammar also honours him with annual scholarships that give students the chance to achieve what he could not.

The Price and Promise of Vision

The legacy of the Slater family is therefore twofold. On one hand, Bill Slater’s fight reveals how planning decisions reshaped the Swan Valley, sidelining communities and ignoring environmental limits. On the other, the memory of D’Arcy lives on through programs that continue to change young lives today. Both stories are a reminder of the costs of short-sighted development and of the enduring value of vision, resilience and community spirit.

Bill and Christina Slater endured what few families could: losing one property to the airport expansion and later watching their Henley Brook estate collapse under the strain of government rezoning and broken promises. That double blow makes their story unique and worthy of recognition.

Their response has been nothing short of extraordinary. In memory of their son Darcy, they built a foundation that has opened doors for thousands of young Australians in sport, the arts and education. Out of personal loss came a legacy that continues to enrich lives across Western Australia.

It’s long past time for the government to acknowledge both the wrongs done and the good given back by the Slaters. A formal recognition (and even compensation) would not erase the past but it would at least make amends for the failures, pressures and neglect that cost this family so much, while honouring the lasting contribution they have made to the community.

.png)