Fremantle Freezing Meat Works

For many years, small private slaughterhouses were scattered across Perth and its suburbs, catering to local communities. Around Hamilton Hill and Bibra Lake there were not only several of these small slaughterhouses but also about ten piggeries.

Even though health inspectors carried out checks and laws were meant to keep standards in place, conditions were often far from clean. Animals were kept in overcrowded, unhealthy and sometimes cruel environments, which encouraged the spread of disease. As Western Australia’s population grew rapidly, the problem became harder to ignore.

There were repeated calls to establish public abattoirs that could enforce proper hygiene and safety rules but progress was slow. Part of the delay came from resistance to breaking up the meat industry monopoly, which was plagued by financial scandals and increasingly difficult to control from a public health perspective. With only a limited number of government health inspectors to monitor so many sites, it took more than fifteen years before serious plans for a public slaughterhouse and freezing works finally moved forward.

Constructing the Works

By June 1916, the majority of Perth’s small private abattoirs had been forced to close, following years of concern about poor hygiene and animal welfare. The final operation, run by the well-known firm Connor, Doherty & Durack, lasted a little longer but was eventually shut down in 1917.

With private slaughterhouses gone, the pressure was on the State Government to create a properly managed, large-scale facility. Western Australia’s livestock industry was expanding quickly, yet the state lacked the infrastructure to prepare meat for export. Local producers found themselves at a disadvantage, struggling to compete with the eastern states where freezing works and abattoirs were already well established.

In response, the Western Australian Government under the Lefroy Government, granted a charter to the WA Meat Export Co Ltd to construct the Fremantle Freezing Meat Works at Robbs Jetty (Owen Anchorage), which was designed by architect McKenzie. By the time works began in August 1919, the Government had been offered control of the abbattoir, which attracted considerable criticism, particularly due to the very large sum of funds involved in its establishment.

It was also known as the West Australian Meat Export Works. The site chosen was steeped in its own history, the grounds of the old Robb Jetty Explosives Magazine. The magazine, which had once stored volatile materials for shipping, was relocated further south to Woodman Point to make way for the new works.

Construction was expected to be completed within a nine month period but it would take a much longer period of time than anticipated. In October 1921, the abbatoir was expected to not be in full swing until the beginning of the following year, due to the low price of meat in England. At the same time, the Wyndham Freezing Works were experiencing their own difficulties with a shutdown forecasted for the near future due to difficulties in attracting labour.

The Fremantle Freezing Meat Works was more than just a slaughterhouse; it represented a turning point in the regulation of the meat industry. Operating under the Abattoirs Act of 1909, it became one of three state-regulated abattoirs (the other two being located in Midland and Wyndham) designed to meet strict health standards, ensure fair access to facilities and strengthen WA’s presence in international markets. It could chill and freeze carcasses so they would survive the long voyage to Europe by sea without spoiling. Whilst the government owned and operated it, farmers, pastoralists and exporters could pay a fee to have their stock processed there for shipping.

Robb’s Jetty was originally too short for large ships to berth close to shore. As a result, cattle bound for the abattoir had to be driven off the boats and forced to swim to the beach, which saw many swept away or drowned. Those that survived were herded into nearby paddocks to graze until it was time to move them to the abattoir.

Calls were made to extend the jetty as early as 1893. The following year, £200 was spent to extend it to 166.1 metres, allowing larger vessels to unload livestock safely onto the jetty itself. Despite its importance, the structure was eventually dismantled during the 1960s.

Transport improved again in 1898 when, after years of lobbying, the government extended the railway line south to Robb’s Jetty. This new connection eased congestion in Fremantle’s town centre and ended the hazardous practice of driving cattle through busy streets to load them onto rail wagons. The line also included a siding for the Fremantle Smelting Works, which had relocated from North Fremantle to take advantage of the improved rail line. In time, each abattoir complex at Robb’s Jetty gained its own siding from the main line, directly linking the precinct with Fremantle for the efficient movement of both stock and processed meat.

Over the decades, the works handled enormous volumes of cattle and sheep from across the state, arriving by ship, barge and later rail. The processing works didn’t just handle meat, it also generated valuable by-products such as hides, wool and tallow (refined animal fat). These were sold to private merchants and fed into other industries, with hides supplying tanneries, wool going to textile buyers and tallow used in everything from soap-making, lubricant and candle production. Beyond livestock, the abattoir also functioned as a cold-storage hub, storing supplies of potatoes, fruit and manufactured ice, which helped service Perth’s growing population and supported local markets.

Potatoes in particular, were being stored to avoid a glut in the market. Some twenty potato growers took advantage of the storage offer, which led to approximately 600 tons of potato being stored there at one time with farmers paying a weekly fixed rate of £21. Despite being stored in a coolroom, it was yet to be made operational, which led to 70% of the consignment being left to rot. Aside from the costs being charged, the farmers were then left responsible for sorting and dumping the ruined potatoes, with some farmers losing virtually their entire stock at a cost of £300.

At some stage, the abattoir passed into private hands and was run as a commercial enterprise until around 1942, when the Commonwealth intervened to provide financial support. As difficulties mounted, the government went a step further and purchased the facility outright. Following the takeover, it was renamed the Western Australian Meat Preservers and later became known as the Western Australian Meat Exporters.

History Today

The abbattoir was permanently closed in 1994, although other sources state that it closed in 1992 and the buildings were demolished in 1994.

One of the most distinctive features of the site was its tall brick chimney, which still stands today as a landmark. This chimney was part of the boiler house, the powerhouse of the operation. The boilers generated steam to drive machinery, operate the freezing plant’s compressors and provide hot water for cleaning and sterilising equipment. Without it, the facility couldn’t run.

When the abattoir closed in 1994, all but the chimney stack were demolished. The chimney stack was spared and preserved as a heritage structure in 1996, with Landcorp funding the chimney’s restoration at a cost of $50,000. It served as a lasting reminder of a site that played a major role in WA’s meat export industry for nearly a century.

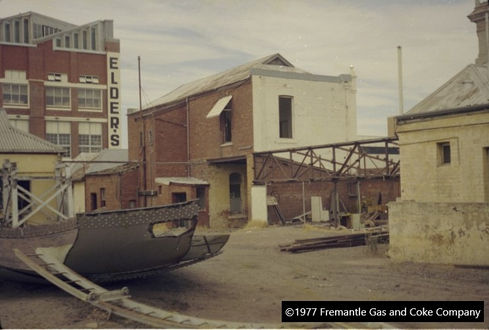

Fremantle Gas & Coke

Long before Fremantle was connected to natural gas or electricity, the town was lit up and heated with coal gas, made right in the middle of town. The company behind it was the Fremantle Gas and Coke Company and its story begins with an engineer named Robert S. Newbold.

Robert Newbold

Robert Newbold, formerly with the Melbourne Gas Company, was sent to Fremantle in 1883 to establish a gasworks on Cantonment Street. It was known as the Fremantle Gas Company, although some sources refer to it as Needle’s Gas, owned by A.G. Rosser.

His initial task was to provide gas for the town’s streetlights but as the network expanded, the supply was extended to homes for cooking and heating. At the time, Fremantle had no public lighting and relied on candles, oil lamps, and kerosene. Within two years, the gasworks had laid more than two kilometres of mains. The arrival of electric lighting in 1904, switched on in an instant, meant there was no longer a need for someone to walk the streets each evening lighting the gas lamps (1).

Although it's hard to find out what kind of training Newbold had, he clearly had the skills and experience needed to design and operate a functional gas plant. He also played a part in the community, serving on the Fremantle Town Council and leading the local volunteer fire brigade.

Raising the Capital

The Fremantle Gas and Coke Company Limited, established in 1885, proposed taking over the Fremantle Gas Company. It was a limited liability company, which allowed people to buy shares and invest, without risking their personal assets beyond what they invested.

A prospectus (an investment invitation) was issued on 29 July 1885 and the first directors met at the Emerald Isle Hotel in Fremantle to get things moving. The company grew through public share subscriptions, people investing money in exchange for a stake in the company.

By 1929, the company’s growth prompted the directors to double the company’s capital, from £30,000 to £60,000, to fund upgrades to the aging plant and to expand its services.

Gas and Coke

As well as producing gas, the company also manufactured coke, a solid fuel made during the gas-making process. The coal was originally shipped in from Newcastle (NSW) and, in later years, brought by rail from the Collie Coalfields. It was heated in large ovens to release gas but what remained was coke, which was sold as a clean-burning fuel for stoves, blacksmithing and industrial boilers.

The gas was stored in large round tanks known as gasometers, which became landmarks in Fremantle until they were removed in the 1970s.

Location

The main gasworks were on Cantonment Street, with the company’s showroom and offices at No. 8 Cantonment Street. In 1953, a new modern showroom building was constructed, where it still stands today. Located behind, was the old Wesley Manse building which was constructed in 1893 and later used by the company as a workshop. Both buildings are heritage-listed and remain in use today, restored and repurposed for commercial use.

A new gas plant was built in Spearwood on a 43-acre site at a cost of £250,000. The facility featured an 80-foot chimney stack, a retort house (the gasworks building where coal was heated in sealed vessel without air, producing coal gas, tar and coke), a 500,000 cubic feet gas holder (also known as a gasometer, a large cylindrical storage tank that holds gas after production), a tank stand and its own water supply. At the time, it was considered one of the most modern gasworks in Australia, supplying gas to the Fremantle district, including Melville, Cottesloe, Peppermint Grove and part of Claremont.

The gas plant operated in Spearwood until its reported relocation to O’Connor in 1976, though no further details about the O’Connor site have been found. The Spearwood site today comprises a housing estate between Angus Avenue and Leonard Way.

Changing Times

The Fremantle Gas and Coke Company remained a major local utility provider for more than 100 years, serving thousands of homes in the Fremantle area but by the 1980s, natural gas had replaced coal gas and the company was no longer needed in its original form.

In 1986, the State Energy Commission of Western Australia (SECWA) purchased the property for $39.7 million, giving its previous owners, Western Continental Corporation a $15 million profit. The transaction later came under scrutiny during the WA Inc Royal Commission, which examined questionable government dealings of the era.

References

(1) Freo: A Portrait of the Port City, Stan Gervas (1996). Gervas Books. p.38

Fremantle King’s Warehouse

The Commonwealth of Australia announces, in an advertisement published on 30 January 1904, that the Department of Trade and Custom's King Warehouse will close, as of 1 March 1904. No further elaboration is given, nor any further ads published in support of this. Either the King’s Warehouse only closed for a short period of time or relocated to a different venue on Cliff Street.

Sometime after this published notice, it appears there may have been another warehouse under the name of Fremantle Bond and King’s Warehouse. It could be the case the Fremantle Bond shared their space with the King’s Warehouse, atleast for some time.

The King’s Warehouse appears to have been used by the Customs Department for seizing and storing cargo and contraband from ships, as well as a general receival and dispatch warehouse for cargo, particularly if payment such as duties was required before being moved.

1901

November 08 – A 21 year old man was charged with unlawfully entering the King’s warehouse, which at the time, was being used by the Department of Agriculture. A railway watchman noticed that someone had forced entry into the premises. He closed the door and placed two guards outside it, before setting off for the police. A short time later, the thief stuck his head out the door and was caught by the two guards. He claimed he was starving and entered the building in search for food.

1904

March 16 – A public auction is held to sell unclaimed goods at the King’s Warehouse, as well as sundry seized and smuggled goods, on behalf of Customs.

1906

September 22 – Burgulars entered the King’s Warehouse and made off with a large quantity of plate stored in bond, valued at £1,000.

November 06 – P&O’s RMS Mooltan was found to have 60lb of tobacco concealed in a linen press. Despite inquiries made to identify the owner, no person came forward and the tobacco was subsequently seized and stored in the King’s Warehouse.

1909

June 03 – Upon visiting an Italian wine saloon on the corner of Wellington and Queen Streets in Perth, Customs officials seized two sacks containing 90 bottles of French brandy, which were discovered on the premises. Around the same time, a visit was made to the storeroom of the Pier Hotel in Fremantle where 11 bottles of the same kind of brandy was discovered. In both cases, the people held responsible were unable to establish a satisfactory reason for possessing the liquor, which would result in charges instigated by Customs.

1911

May 25 – The mine sheds located on Fremantle’s wharf are identified with letters ranging from A to I. At the end of Victoria Quay, there are more storage facilities. Located on the northern side of the river is the bond shed, the King’s warehouse and the fruit shed.

The officer based at ‘C’ shed is required to attend the King’s warehouse, the Bond shed, the fruit shed, A-D sheds and often the E shed as part of his duties, with a total staff count of five. One of the other staff members is responsible for attending the Port parcels office on a daily basis, which tends to take up to four hours of his time. Two staff members are cadets, which limits their duties to luggage and delivery, with the two remaining staff being juniors, who “can only assist the examining officer under direction”. The sheds are burdened with mail, overseas passengers and foreign boats importing thousands of tons of cargo, which taxes the time and resources of the limited staff members.

1912

May 8 – Alterations are made to the King’s Warehouse for printing of stamps and Australian notes.

1913

The Custom’s Department leases King’s Warehouse to the Royal Australian Navy.

1915

February 25 – Alterations to the King’s Warehouse at a cost of £444 is complete.

1926

October – The District Naval Officer and his staff vacate King’s Warehouse to move into the newly constructed Drill Hall on Mouat Street, which is officially opened on October 8.

.png)